Tony Velona was another lyricist I hooked up with as a songwriting partner, but in his case, I had a different objective in mind.

This was in the later 1960s when all of us in the music business knew that rock music was here to stay. It had become the dominating commercial music in every respect. By then, jazz occupied an even tinier niche than usual. Jazz clubs in America were down to a precious few, and it was difficult, if not impossible, to make a living as a jazz musician. As for songwriters who worked in the traditon of the Great American Songbook, they couldn't get arrested with the tunes they wrote. People like Johnny Mercer looked on me as the younger guy coming along in their footsteps. That was what I was prepared for both by training and by instinct. But the time for that music seemed to have passed. Now all it took to become a rich and famous songwriter and performer in the rock era were a guitar and three chords.

I decided to take an attitude along the lines of, if I couldn't beat them, then I'd join them. Or at least I'd make a subtle nudge in rock's direction. With that purpose in mind, I hooked up with this fine lyric writer, Tony Velona. I met Tony through his brother-in-law Teddy Sommer, a New York drummer I had worked with. Tony and I agreed we might be able to write music in a form that would appeal to young rock-minded listeners. That was the plan.

Tony, a guy from New Jersey who settled in L. A., had earlier written a tune called Lollipops and Roses, which turned into a massive hit in 1962. All kinds of people recorded it. Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, Natalie Cole, even Doris Day, were among them, and Jack Jones won a Grammy for his version of the song. It was a hit that made tons of money for all concerned.

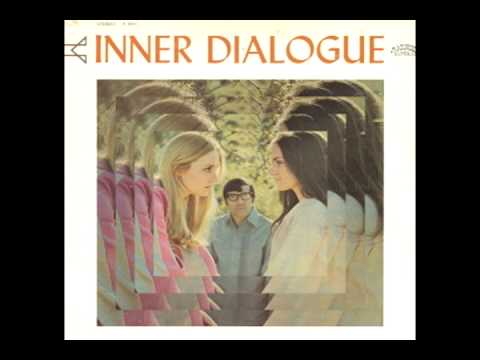

Together, Tony and I wrote thirty or more songs. The way we operated was that I came up with the melody first, and Tony, who had a really agile mind, conceived lyrics that went with the melody line no matter how complex the line was. He was outstanding in his skill with words. Even the name of our group, Inner Dialogue, came from one of his lyrics.

We had the songs, and we put together the band that presented our material. The band consisted of Barry Zweig on guitar, Jerry Sheff on fender bass (he left us when Elvis Presley offered him a phenomenal fourteen hundred dollars a week, and we brought in Ernie McDaniel as Jerry's replacement), Bob Lanning on drums and me on piano, plus two dynamite girl singers, B. J. Ward and Lynn Dolin. It was the two girls that helped make us different. Rock was a kind of music where almost all the people who sang, played in bands and got attention were guys. Our two girls had fabulous voices and great pedigrees in music. Lynn's father was Jerry Dolin who was the great songwriter Frank Loesser's right-hand man, and B.J. was married to Don Trenner who led the band on the Steve Allen TV show.

We got much of our financial backing to launch the group from Raquel Welch and her husband, a guy named Patrick Curtis who was also Raquel's agent for a time. My hookup to Raquel and Patrick came about when they hired me to help with her singing, the same as I'd done with Lucille Ball and a few other women performers. My coaching became particularly valuable for Raquel in a trip to London where she was making a TV special with Tom Jones.

The deal for me in London wasn't just to give Raquel vocal guidance but also, as things developed, to act as a referee in the Welch versus Jones combat. The two of them, Raquel and Tom, took an instant dislike to one another. Maybe it was because each was a big sex symbol of the day, Raquel for the guys and Tom for the ladies. Whatever the reason, there was plenty of tension on the set where we shot the TV show, and it was somehow left to me to keep the peace. I pretty much held up my end of the bargain because the special got made, and it wasn't bad. I think Raquel appreciated my contribution. That may have been part of her motivation in chipping in financially to get Inner Dialogue off the ground.

YOU ARE READING

I Can Hear The Music: The Life of Gene DiNovi

Non-FictionGene Di Novi played piano for the greats of the 20th Century: Lena Horne, Peggy Lee, Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker. This is his biography spoken to the fine writer Jack Batten. "I played piano with Bird and Diz...