I also had an older brother: Russell Meeks. He was seventeen, a senior at my same school, Evergreen High. He was working on his college applications, so that's what we talked about at dinner that night. Russell was very smart and ambitious. He wanted to be a lawyer, like my dad, so there was a lot of focus on what college he would go to. The Ivy Leagues were what everyone was thinking, since they're supposedly the best.

I ate and listened. My brother had recently started talking in a new way. It was a very clear and careful way of speaking, but it also had this special nasal quality to it, like he was smarter than you, like you probably wouldn't understand what he was talking about, that's how smart he was. Nobody else in my family mentioned this new tone. Maybe they didn't notice it. Or maybe they accepted it as part of Russell's gradual changing from normal kid into Ivy League college student.

It was mostly him and my dad talking. My dad had gone to college back East. And then to New York City for law school. He always brought this up when he talked about his past. What New York was like. How different it was from Portland, Oregon. How you didn't know how the world worked until you'd lived back there, where the important people were, where the real stuff happened.

Anyway, Russell was saying something about a friend of his who was applying to Cornell. So then my dad had to give his opinion on that. They got in a big debate about which was better, Harvard or Stanford or Cornell. That's when I realized Russell had learned his new tone of voice from my dad. It wasn't the exact same style of talking, but it conveyed the same basic message of I'm a douche bag.

As she cleared the table, my mother brought up the news about Antoinette. So then I had to talk. I told about the suicide in my mumbling way, which, as usual, drove my father crazy. "Speak up, Gavin!" he said. "Nobody can hear you!"

"I said," I repeated. "That a girl in my grade got taken out of class because her brother killed himself."

"Was that the jumper?" said Russell. "I heard about that. The guy who jumped off the Vista Bridge?"

I nodded that it was.

"Do you know this girl?" said my dad.

"No," I said.

"Who's she friends with?" asked my mother.

"Nobody, really. Her family just moved here."

"That's so sad," said my mother.

"Who are his parents?" asked my dad. "What do they do?"

"What difference does that make?" I mumbled into my plate.

My dad didn't bother to answer. This was the kind of thing he hated to talk about. Suicidal teenagers. People who had problems. People who weren't achieving and succeed- ing and going to top colleges and New York law schools. Russell, too. They would much rather go drink brandy in the den and talk about whether Cornell was better than Stanford.

After dinner I went upstairs to my room. Tennis was my thing. That was where I'd achieved and succeeded. I'd won a bunch of local tournaments in the twelve and unders, so my room was like that: a bunch of trophies lined up on a shelf and my walls covered with posters of my favorite tennis stars. Roger Federer. Andy Roddick. Rafael Nadal. There were lots of Nike swooshes everywhere. Sometimes at night I'd practice my serving motion in my room, while I listened to music. Sometimes I would bounce a tennis ball on my racquet face. I had once done that 1,217 times in a row, which was still a record at my tennis camp.

But that's not what I did that night. A couple weeks before, my mother had bought some old art books at a rum- mage sale. One was a book of landscape paintings from the 1700s. These showed scenes of cows and fields and little valleys. I'd brought this book up to my room and cut out one of the pictures and thumbtacked it to the wall above my desk. I did this as a joke, really. I wasn't into art. I just felt like looking at something different for a change.

But that night, after the encounter outside Antoinette's house, I found myself looking through the art book again. And then I decided to take down my Roger Federer poster. I was bored with it. I unstuck it from the wall and went through the art book and found two more paintings that I liked, one of a road going past a farm, with a huge sky and clouds above, and another of a harbor, which also had clouds and a big sky. I cut them both out, trying to keep the cut line as straight and neat as I could. Then I thumbtacked them to the wall where the Roger Federer poster had been, one on top of the other, keeping them just the right distance apart.

Once I'd done that, I started looking at my other posters. One of my oldest ones showed the history of tennis in the United States. It was pretty lame, with all these old dudes and their old-style shorts. So I went back to the art book with my scissors and slowly turned the pages, looking for something to replace it.

I was listening to the college radio station while I did this. They were playing good electronic stuff, like they do at night. So I had this fun night of redoing my room and listen- ing to music and cutting these pictures out of this art book. The other thing was: I kept thinking about Antoinette. Not like anything in particular, just having her in the back of my mind. As the night went on, I realized I was doing this for her. I was making my room into something she would like.

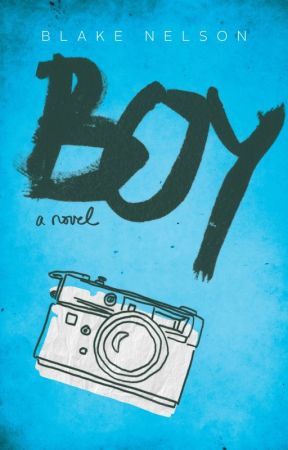

YOU ARE READING

Boy by Blake Nelson

Teen FictionEvery Tuesday and Thursday, we're posting a taste of Blake Nelson's BOY, his brand new novel that's on sale now! If you've got questions or comments for Blake Nelson, post away-he'll be periodically checking Wattpad and responding! In the style of...