On the first day of June, my mother knocked on my door and told me my dad wanted to see me on the deck. That didn't sound promising. I went downstairs and found him sitting outside, in the late-afternoon sun, having a drink. I could tell he was going to lecture me about something, but I didn't know what. My brother had been accepted to Cornell University by then. Maybe he was going to gloat about that. Or maybe he wanted to discuss my 2.8 grade-point average and my nonexistent extracurriculars.

I paused at the sliding glass door, to watch him. My father was still wearing his suit and tie. The tie was loosened and pulled over to one side. He swirled the ice cubes around in his glass. It occurred to me he might be drunk.

I slowly pulled the door open. I wasn't looking forward to this

"Come out here, Gavin!" boomed my father. "I want to talk to you."

I went outside and sat down across the table from him, in one of the deck chairs. We hadn't cleaned the outdoor furniture yet. It was still dirty from the winter. My dad didn't seem to notice. I could see some of the dirt from his chair had gotten on his suit.

"So your mother tells me you're not playing any tennis tournaments this summer."

This was true. I had dropped like a rock in the state tennis rankings over the school year, partly because I had skipped most of the big tournaments, but also because I was in the sixteen and unders now. Other guys had begun to emerge at this new level, guys I had been able to beat in previous years but who had suddenly grown four inches, or hired better coaches, or who knows what. There were also new people, superior athletes, who had for some rea- son picked up tennis racquets. I had been ranked as high as #2 in the state in the twelve and unders. I had dropped to #11 in the fourteen and unders. Now, in the sixteens, I was ranked #94 or something.

"I think I want to try other things," I told my father.

"And what other things do you want to try?" he said, slurring his words slightly. "What else exactly are you good at? Besides tennis?"

"I don't know," I said slowly, carefully. "That's what I want to find out."

My father took a sip of his drink. He stared out into the large yard of the large house he had bought for our family, which Russell and I had grown up in.

"Mom says you've dropped in the rankings."

"I have," I said calmly.

"And why is that?"

"The other guys have gotten better."

"And you have no problem with that?" he asked.

"There's nothing I can do about it."

"You could get better yourself."

"There's a certain factor of talent," I said coldly. "I'm good. But some people are really good. I can't beat those people. No matter what I do."

"So you say," grumbled my father.

"Those are the facts of it."

"Those are your facts of it."

I sat there. I stared into the yard.

"There's something about you," said my father. "Something I've been trying to figure out for a long time now. And I think I know what it is. I think I've finally put my finger on it." He paused dramatically, then turned to look me in the eye. "You think you're better than other people."

I sighed and stared into the yard.

"And you know what?" continued my father. "That is about the worst quality a person can have. If you were a great tennis player, then maybe you could have an attitude like that and get away with it. But as you've just said yourself"—he sipped his drink—"you're not a great tennis player."

I said nothing.

"I wish I knew what to say to you," said my father. "I would tell you to look to Russell. To learn from your brother.

To see how a person can be confident and still not alienate the people around them. It's the difference between confidence and arrogance. A confident person, other people will rally around. But an arrogant person . . ."

He was right. I was arrogant. And difficult. And defiant. But it was only with him that I was like that. I wasn't like that around other people. Other people liked me just fine.

"The problem with you is . . . ," said my father. He stopped to consider the best way to describe the problem. "You don't think about the other guy. Now, maybe you can find a job working in some remote location. Or sitting in a cubicle. But those aren't good jobs. Trust me. Good jobs require dealing with people. And if you've got an attitude, who will want to deal with you?"

"Russell's the one who thinks he's better than everyone," I said quietly.

"Russell . . . ?" said my father, his nostrils flaring suddenly. "I'll tell you something. Russell is going to be very successful. He's going to do better than I've done. And I've done pretty damn well, as you can see from where you're sitting at this moment." My father waved his hand to indicate our large house and yard. "I don't have any idea where you're going to be sitting in twenty years," he said. "Not anywhere good, at the rate you're going. Which is what I'm trying to tell you."

He's drunk, I said to myself. I sat there. I bounced one of my knees up and down. A warm breeze blew across the yard. Bits of sunlight peeked through the maple trees that divided our property from the Winslows'.

"So what are you going to do with your summer?" said my father. "If you're not going to play tennis?"

I'd thought about this already. My mom had found me a job at the Garden Center, which was a local nursery owned by one of her friends. And the other thing was, my brother had a fancy camera he'd gotten for Christmas the year before and had never taken out of the box. During my landscape painting phase, I'd convinced him to let me look at it. It was complicated, but I'd figured out the basics. What I hadn't done was take it outside and actually try it.

"I'm going to take pictures," I told my dad.

"Take pictures," he snorted. "Like what? With your phone?"

"With Russell's camera."

"And why are you going to do that?"

"Because that's what I want to do," I said.

"Oh, good," said my father. "Only do what you want to do. That's a good strategy. The world always needs more people like that. I can see the ad now: 'Wanted: Person who only does what he wants to do.''

My dad laughed at his own joke. He took a long swig of his drink.

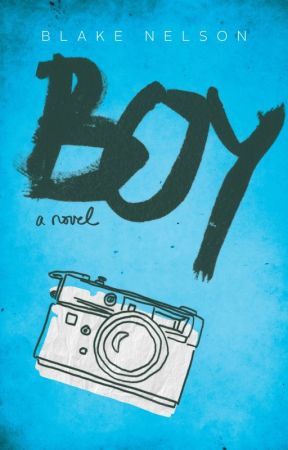

YOU ARE READING

Boy by Blake Nelson

Teen FictionEvery Tuesday and Thursday, we're posting a taste of Blake Nelson's BOY, his brand new novel that's on sale now! If you've got questions or comments for Blake Nelson, post away-he'll be periodically checking Wattpad and responding! In the style of...